Egginton through the ages

Early History

After the Roman invasion of AD43, the legions constructed strategic roads across the country, one of which was Rykneld Street, now known as the A38. The area was probably thick scrub and forest or marshy grass, frequently flooded by the Dove and Trent. As late as 1769, a considerable length of road could still be seen on Egginton Heath, before being obliterated by making the turnpike.

After some 300 years the legions were recalled to Rome, leaving the country open to raids from Angels, Saxons and Jutes from across the North Sea. When they started to settle, felling trees to build houses and to clear the land, they would choose a site well away from marauding bands. Such a settlement was called a ‘tun’ or farmstead. In this case the farmstead of Ecga, or Ecga’s tun. He was thought to have been an Anglian from the 6th Century, around approximately the same time that St.Wilfrid, patron saint of Egginton church, was Bishop of Mercia.

The Danes soon followed, plundering and destroying and finally settling and becoming christianised. When the Domesday Book was prepared in 1086, for taxation purposes, EGHINTUNE had land for 6 ploughs, a priest, a church and a mill. Egginton passed through several owners over the years, while remaining a quiet and largely untroubled village.

Local names provide a further reminder of our past. Salters Way and Saltersford bridge, near the Hilton railway crossing, remind us that salt from Cheshire would be carried by pack animals to markets throughout the country. Salt being a vital commodity for preserving food through the winter months. ‘Coal pit way’ is a reminder that the track now running from High Bridge over the canal towards Newton Solney forded the Trent to get to the coal pits around Swadlincote.

16th Century

The Wars of the Roses seem to have left Derbyshire fairly unscathed. Not so the Reformation. The dissolution of the monasteries 1534-1538 not only involved the local houses like Burton Abbey, Tutbury Priory and Repton but also the Abbey of Dale. (During the Middle Ages, along with other villages, part of the tithes of Egginton were gifted to the Abbot of Dale Abbey (between Derby and Ilkeston), to allow the monks to provide hospitality to the many travellers who sought shelter. In such ways did monasteries became immensely wealthy.) In 1538 the Abbot and his 16 canons signed the Deed of Surrender to Henry VIII. Had they not surrendered, their fate might have been like the Prior of Beauvale who was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn in 1539.

It is difficult to understand what a shock to the country the dissolution and destruction of the religious houses must have been. They had been responsible for most of the education, the care of the sick and elderly and whatever social services were needed. They gave hospitality to travellers and sanctuary to fugitives. Dissolution resulted in a lot of general lawlessness. The Every papers of 5 July 1542 record the enquiry into 5 named individuals of Egginton who ‘with sticks, swords and knives assembled at Egynton and under the order of Humphrey Babyngton Esq, broke in to the close of Thomas Rolleston of Egynton and riotously cut down and destroyed the grain growing and committed other enormities…against the Kings peace.’

One of the Babington family with interests in Egginton was the Roman Catholic Anthony, who was page to Mary Queen of Scots when she was held in Sheffield Castle. He became involved in the plot to murder Elizabeth and put Mary on the English throne. With other conspirators he was hanged, drawn and quartered as a traitor at the age of 25 in 1586. Mary’s scheming resulted in her being held prisoner for several years at Tutbury Castle, amongst other places, before her execution in 1586.

Interestingly Queen Elizabeth I granted Sir Walter Raleigh some land, including a fourth turn of presentation to the church at Egginton. By this time the main landowners were the Leigh family. They are recorded as giving £25 towards a collection to defy the Spanish Armarda in 1588. On the death of Sir Henry Leigh, Egginton Hall passed to his daughter Anne, who had married a young man from Somerset, Simon Every.

17th Century

The manor of Egginton and sub-manor of Hargate (or Heath-Houses) was divided by the Dove (as in ‘stove’ not dove as in ‘love’) and the Hilton and Egginton Brooks. To the north Egginton Common adjoined Etwall Common. Flooding is thought to have been a regular occurrence. The Trent was not polluted and a 26lb salmon was recorded in the Dove in 1774.

The slightly higher land was used for growing crops, each man being allotted cleared unfenced land in a strip, suitably for ploughing in a day. (Look at the map in the church showing many of the old field names). Ordinance Survey maps continue to mark the old osier beds, a type of willow used in basket making, which was a profitable local industry. The area was also known for its milk and excellent cheeses.

Simon Every came from an old family who had originally come from Ivry in Normandy. Having married Anne Leigh in 1628, he came into the estates of Egginton and Newton Solney. He became a magistrate for Derbyshire in 1636 and later created a Baronet by Charles 1 in 1641, for services to the King. He was also appointed Receiver general of the Duchy of Lancaster with Sir John Curzon.

When the Civil War began in 1642, Sir Simon is said to have been in charge of munitions and supplies for several Royalist Castles, including Tutbury. The largest battle to be fought in Derbyshire was in 1644, known as the battle of Egginton Heath. The Royalists were returning victorious from a famous victory at Newark and were surprised on Egginton Heath and put to flight by the forces of the Parliamentarian, Sir John Gell of Hopton. The Royalists fled through the village of Egginton, with many being killed trying to ford the Dove and Trent to escape their pursuers. Around 250 years later, a beautiful Cavalier sword was found in the thatched roof of an old cottage being pulled down on the corner of Main St and Fishpond Lane, known as Greg’s cottage.

It was a serious disadvantage supporting the losing side. For the next two generations Sir Simon’s family sought to avoid the Commissioners for Sequestrated Estates, eventually settling for a fine of £2,000. (Now around £185,000 ! ).

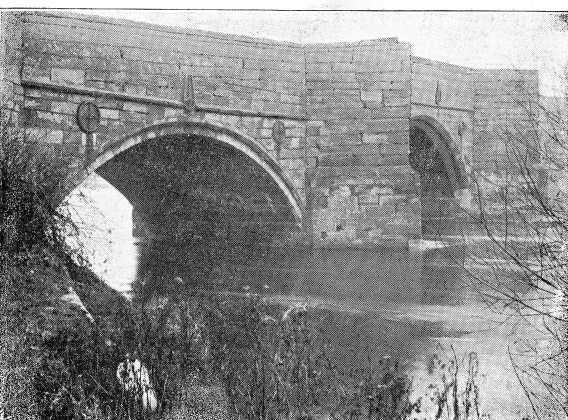

Monks’ Bridge was thought to have had Roman Foundations but the earliest known reference to it is around 1200 when John de Strettone, Prior of Burton Monastry was granted funds from the Monastry to construct a bridge over the Dove. After his death, the inhabitants of Egginton asserted that the Abbot of Burton should maintain the bridge in perpetuity. King Henry III called for an inquiry but this achieved little as the next reference is to the sale of Egginton’s Church bells to meet the cost of repair bills of 1553 for work done four years earlier. Numerous repairs were recorded between 1683 and 1775 when the bridge was repaired and widened. In that year Sir John Every 7th Bart and Francis Ashby were ordered to pay £451 for the work (equivalent now to around £34,000). The old bridge survived the rise and fall of the Turnpike until it was eventually by-passed by the new road bridge in 1926.

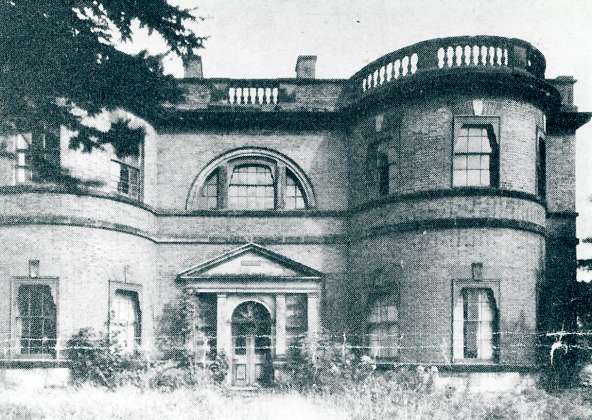

A terrible fire destroyed much of the Tudor Hall in 1736. After several false starts and much delay, it was rebuilt around 1780 by Sir Edward Every 8th Bart to a design by James Wyatt, who also designed Shugborough Hall. The new Hall was built in the fashion of the times in that it stood alone except for its stable block. The surrounding cottages of wattle and daub were cleared away to provide a fine 50 acre park with lake, known as ‘the fishpond’.

New houses and farm buildings, built in brick, were sited along Main Street, Duck Street and Fishpond Lane, which surrounds a slightly higher piece of land believed to have been the original site of the early settlements.

The major dwellings had a small piece of land enclosed for garden crops and handy for rearing calves. These enclosures were known as ‘crofts’. The field map shows examples of names such as Flax Croft, Far Croft and Rye Croft, which are retained in the names of certain houses. So the process of starting to fence in open land was happening in Egginton well before the Egginton Enclosure Award completed in 1791.

At this time Egginton was a ‘closed’ village with all the houses and farms owned by the Estate and let to tenants, most of whom would have worked on one of the 11 farms or supplied food, clothing or other services to the community. A pair of early Georgian stone lodge gates were sited at the end of Lodge Lane, now called Church Road, next to the A38, forming the entrance to the Hall and the village.

Progress was on the march. The River Trent was made navigable from its mouth to Burton-on-Trent in the early 1700’s and in 1766 an Act was passed to make a canal joining the Trent and Mersey, which took 11 years to complete. The ‘navvies’ were a tough lot, who terrorised the countryside poaching and raiding poultry. Wharfs were constructed at Willington and Clay Mills and the house by High Bridge was probably built as an alehouse to refresh bargees. Until the coming of the Railways some 70 years later, the canal carried most of the heavy traffic as well as a few passengers.

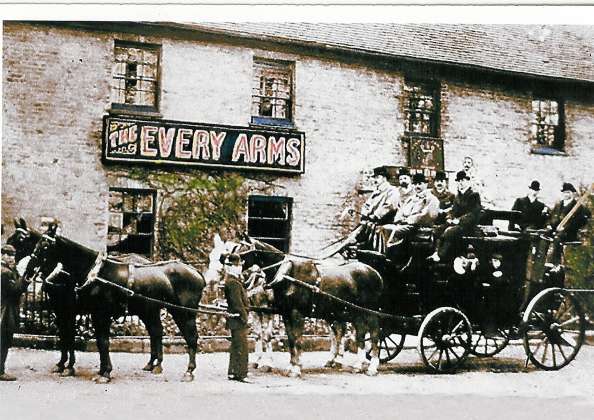

At much the same time efforts were made to improve the roads by a series of Turnpike Acts. These set up Trusts to repair and widen the road from the west end of Burton to the south end of Derby, funded by tolls. Rykneld Street then enjoyed the heyday of the coaching era between Derby and Birmingham. The coaches and their teams of horses, beautifully turned out, were not always comfortable or safe. Winter journeys must have been agonies of cold and cramp. Travellers would thankfully reach a hostelry and refresh themselves while horses were changed. The Every Arms served this need. The field opposite was called the Coach field, perhaps after its former name the ‘Coach and Horses’.

19th Century

The row of white cottages opposite the park wall in Fishpond Lane were built with their doors at the back, as were two other rows of cottages, one of which survives up by the bridge, off William Newton Close. In 1815, Squire Osbaldeson of Atherston leased the land at Egginton for a hunt. Not being a good sportsman, he contrived to call off the hunt just when the hounds had put up a fox in one of Sir Henry’s coverts. Sir Henry’s lecture on sportsmanship was not well received and a few days later was followed by a challenge to a duel. Duelling was illegal and his friends (supported by the Hunt Committee) persuaded him not to accept the challenge. But the incident preyed on his mind and when he came to build the new cottages he did so with their doors at the back so he would not see his tenantry gossiping about him on their door steps as he drove past in his carriage.

In 1829 the Parish was said to comprise 2,291 acres and a population of around 300. The main occupation was agriculture, the land being chiefly meadow and pasture. Wages were 9 to 10 shillings a week (£23pw). The most substantial tenant on the Estate with 248 acres, was Luke Ashby, whose memorial is situated in the north aisle of St Wilfrid’s Church.

The next excitement was the coming of the Railways. The Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway Company was founded in 1837. George Stephenson surveyed the route – at first from Derby, through Burton and Tamworth to Stetchford to the south of Birmingham. The Company being fearful of rivals, the line was quickly built. By 1844 several competing companies had amalgamated to form the Midland Railway.

A year later the North Staffordshire Railway Company was incorporated. Three Acts of Parliament had been obtained to build the new railway, the only disappointment being that a branch between Marston and Willington had been opposed by Sir Henry Every 9th Bart, but by 1849 he had relented and this line too was built. Our local station being Egginton Junction, next to the Hilton crossing. The horse-drawn barge of the canal and the horse-drawn coach of the turnpike steadily lost their trade to the iron horse of the railways.

Some years after Rowland Hill’s penny postage was introduced in 1840, a rumour circulated that an austere father would not permit his daughter to marry unless she first collected one million postage stamps. This unlikely story became attached, wrongly, to Miss Penelope Every, daughter of Sir Henry Every 9th Bart. Boxes, parcels, baskets and crates of used stamps started to arrive at Egginton Junction in large quantities requiring wagons to be sent to the station to collect them. Eventually the cost of cartage become more than a joke and Sir Henry wrote to The Times proclaiming that sufficient stamps had been collected. The stamps were stored in the attics at the Hall and, on wet days, the children would play with them, throwing them about like Autumn leaves. By the latter part of the century the maids had become unsatisfied by having to clear up the mess on repeat occasions and, having complained to the Head of the Household, the whole lot were taken out by the gardeners and burnt. What would thousands of Penny Blacks been worth today?

The Directory by Bulmer & Co of 1895 mentions that the school was built in 1857 and enlarged in 1891 and had 84 children on its books. So overcrowded classrooms are not new.

The pinfold or village pound is the only stone building except the church. Here straying animals were shut up (impounded) and held until the owner bailed them out, to the profit of the community. Though no longer used for this purpose, it is to be hoped that this strange part of our local history will survive even the demands of road widening.

In 1855 the Derbyshire Advertiser recorded the death of John Tatum, who had lived in Egginton and invented the percussion gunlock and also a button that needed neither a buttonhole or thread (brass popper?).

Heavy industry also came to Egginton – an ironworks where scrap iron was smelted and forged under a huge hammer mill – worked by a water wheel. This was at Cliffe Milne on the Dove bordering Stretton and Egginton, where a water mill grinding corn was recorded in 1324. The iron industry ceased in 1924 when the works turned to grinding materials for pottery manufacture. Today from the Dove at Egginton comes a large proportion of Leicester’s water supply.

20th Century

Perhaps Egginton Hall reached its zenith in 1902 when it was visited by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra on their way to Doncaster Races. One can imagine the feverish activity of painters and decorators, gardeners and grooms and the household staff to achieve perfection for this great occasion, including no doubt a Triumphal Arch of Welcome raised above the lodge gate.

But perhaps a vengeful uninvited fairy godmother crept in amongst the guests uttering curses of wars, inflation, financial disaster, soaring taxes and death-duties, for 53 years later the Hall was a heap of rubble in a derelict park.

- The Hall was mainly let out, with the Estate being managed by an Estate Manager.

- During WW1 Col Dugdale made the house available for the war wounded.

- A major flood in 1932 surrounded the village, doing a great deal of damage.

- Following financial difficulties the Estate was sold in 1940, bringing the ‘closed’ village to an end.

- In WW2 the Hall was first taken over by the Army and later by the RAF. Bomber Harris of Northern Command would visit Egginton and plan his bombing raids over Germany.

- After the War the Hall became a Local Authority home for the homeless.

Years of neglect during the war and other untreated damage meant that the Hall was no longer weather proof and after the war there was not the money, materials or inclination to do up large houses. As a result it was pulled down in 1954.

Another major flood in 1964 led to the building of a flood bank around the village in 1967, which succeeded in keeping further floods at bay.

The building of two sets of Council Houses and the Elmhurst Estate, while not popular at the time, added greatly to the ability of Egginton to continue to survive as a vibrant and friendly village, retaining its Primary School, Shop and a partial bus service when many villages has long since lost theirs.

1994 sees the start of the building of the new Egginton Hall.

Egginton celebrates the passing of one Millennium and the hopes for the next

21st Century

2002 Egginton celebrates HM Queen’s Golden Jubilee

2007 Shop cum Post Office closed

2008 Memorial Hall refurbished with new Willow Hall at a cost of £446,000

2012 Egginton celebrates HM Queen’s Diamond Jubilee

2015 Flood bank improved with access roads to village raised

2016 New Village signs erected and trees planted along Church Road, Ash Grove Lane and Etwall Road

2017 Egginton bridge refashioned

And the Future? Whatever it is, it is up to all of us, as Egginton residents, to nurture and support this wonderful village community.

Acknowledgement is given to the late Jack Henderson, who wrote the excellent booklet “Story of Egginton and St. Wilfrid’s Church”, from which these extracts are taken. You may purchase a copy from the church.